Many fortunes were made (and lost) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Names such as Andrew Carnegie, George F. Baker, William Rockefeller, and Henry Ford readily come to mind. But what about women? What about Black women?

Hannah Elias is not exactly a well-known name, but by the early 1900s, she had built a real estate empire in New York’s Harlem and amassed a fortune worth more than $1 million (almost $33 million today). Not bad for a “courtesan” and ex-felon.

Elias was born in Philadelphia to a Black/Indian caterer and an “almost white” mother in 1865. At sixteen, Elias went to jail for theft of a ball gown belonging to her employer. After serving her sentence, she supported herself for a time by working as a sex worker at a “resort” in Manhattan’s Tenderloin neighborhood. There, she met wealthy glass-factory owner John R. Platt, forty-five years her senior with whom she would have a secret relationship for many years.

Platt would later tell a court that their paths crossed again in 1896 when he went to a massage parlor (because of rheumatism, he said), and at this point he became “interested in her welfare.” In fact, Platt set her up in a boarding house business on West 53rd Street and gave her enormous sums of money, which allowed Elias to move into a Central Park West mansion while continuing her businesses. There she reportedly passed herself off to her neighbors as Sicilian, East Indian, or Cuban. In 1903, Cornelius Williams, a former boarding house tenant and jealous admirer of Elias, mistakenly murdered city planner Andrew H. Green, thinking he was Platt. Prodded by his family, Platt told a New York court the following year that Elias, whom he called “his ebony enslaver”, blackmailed him out of $685,385 ($22,509,583.59 in 2022 dollars), by threatening to reveal the sensational circumstances of the murder to his family and newspapers.

Her arrest made the headlines. and arraigned in Tombs Court on June 10, 1904, where she was held on $50,000 bail. The story spread, leading to detailed court coverage in the Baltimore Sun as she took the stand and described how her money was kept in “15 savings banks” as well as “houses and lands worth $150,000, furniture and plate, worth $100,000, and jewels valued at as much more.”  At the arraignment Platt — now 84 and clearly under the hectoring pressure of his children to pursue the case — appeared confused and embarrassed at having to testify, and in the end stubbornly refused to admit to being “bled.”

At the arraignment Platt — now 84 and clearly under the hectoring pressure of his children to pursue the case — appeared confused and embarrassed at having to testify, and in the end stubbornly refused to admit to being “bled.”

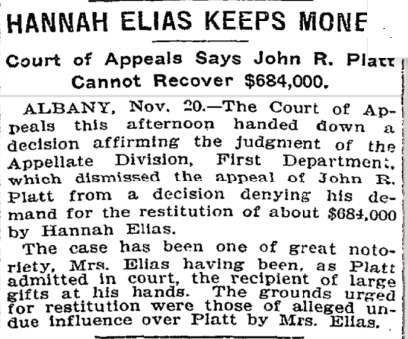

Elias won the case in court. Reports said Platt was jeered when he left the courtroom. His family, however, went on to file a civil suit against Elias. That court case in 1905 also made headlines as people learned of how Elias became Platt’s mistress and how Platt allegedly paid $20,000 to the lawyer who secured her divorce from an early marriage to a man named William C. Davis, a Black man. Elias, represented by former New York state governor Frank S. Black, insisted that she had been Platt’s devoted mistress and friend, pointing out that he had even given her his deceased wife’s watch and pocketbook.

Elias won the 1905 case as well when the court ruled that there was no proof of threats. It also said judges “did not have the duty of enforcing immoral contracts.”

After the two trials, Elias moved to Harlem, where she helped John Nail, a Black real estate developer, turn the neighborhood into an enclave for New York’s Black residents. She later left for Europe, never to return.