Closed Room mysteries appear regularly in mystery novels, but what about real-life examples?

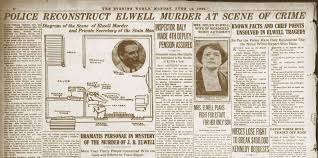

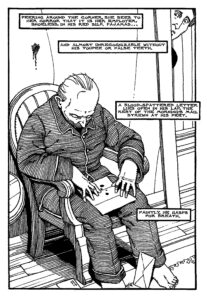

On June 12, 1920, around 9 a.m., a housekeeper unlocked the front door to the West Seventieth Street apartment of self-made millionaire Joseph B. Elwell. There, inside the living room, she found a body sitting in a chair with a gunshot to his head. Beside his chair was a pile of letters.

At first, the housekeeper thought the body was a stranger. After closer scrutiny, she realized it was Elwell without the wig and dentures he wore in public to enhance his appearance.

Elwell, 44 years old, was a recognized authority on whist and bridge. He owned more than twenty racehorses and was a successful financial speculator, as well as a gambler and well-known womanizer.

Police rushed him to Bellevue Hospital, but he died without regaining consciousness or uttering a word.

The crime scene stumped the police. The doors showed no evidence of tampering, and all the windows were firmly shut from the inside, secured with iron grills. No gun was found at the scene, but the murder weapon appeared to have been fired at a distance of 3–5 ft away. While it was possible that the bullet ricocheted off a wall, police ruled out suicide as its placement looked staged. The bullet’s cartridge was lying on the ground. Forensics determined the single bullet came from a .45 Colt pistol.

NYPD surmised Elwell had been opening his morning mail when he was shot. Blood splatter suggested the killer had crouched in front of Elwell when he pulled the trigger. Nothing was stolen, and no unexplained fingerprints were found at the scene. There was no sign of a struggle or forced entry into the house. There was no weapon, no footprint, no evidence of a struggle, no possible clue except the single large-caliber shell, and the stub of a cigarette different from those Elwell habitually smoked.

The New York County District Attorney stated Elwell was chatting in his apartment just before he was shot, and probably knew his murderer. The perpetrator’s sole purpose was to kill him, as nothing was stolen. In fact, valuables were strewn around Elwell’s corpse.

Investigating further, police discovered a vast collection of women’s underwear that Elwell had seemingly taken as trophies from his sexual conquests. Alongside his mementos, they found a list of fifty women he’d engaged in affairs with, each woman cataloged with her name, number, and personal notes. Many of these women were rumored to have been given keys to the house while officially only Elwell and the housekeeper had access. Despite working their way through more than 1,000 suspects, including the victim's soon-to-be ex-wife, the list of girlfriends and their own associates, angry husbands and relatives. All were eliminated as viable culprits.

Investigating further, police discovered a vast collection of women’s underwear that Elwell had seemingly taken as trophies from his sexual conquests. Alongside his mementos, they found a list of fifty women he’d engaged in affairs with, each woman cataloged with her name, number, and personal notes. Many of these women were rumored to have been given keys to the house while officially only Elwell and the housekeeper had access. Despite working their way through more than 1,000 suspects, including the victim's soon-to-be ex-wife, the list of girlfriends and their own associates, angry husbands and relatives. All were eliminated as viable culprits.

Bringing up nothing on the theory that Elwell’s sex life had brought about his end, the NYPD scoured his dealings and associations in horse racing, bridge, and the stock market, again finding nothing that may have led to his demise. He owed no significant money and the police could find no threats made against him. The case went nowhere.

Despite all the evidence collected by the investigators, they were never able to determine who shot Joe Elwell. The case remains an unsolved mystery.

Fun Fact: This classic "locked-room murder" was the inspiration for S.S. Van Dine's The Benson Murder Case (1926), which introduced his famous fictional detective Philo Vance.