What does that jingle evoke in your mind? Chicken noodle soup and a tuna sandwich (my fave as a teenager)? Tomato soup and grilled cheese?

Whatever your favorite, you have John T. Dorrance to thank.

Dorrance, Pennsylvania-born and an MIT graduate, received his PhD from the University of Göttingen, having specialized in chemistry, mathematics and physics. While in Europe, the popularity of soup — a staple item of people’s food there — had impressed him, and he determined to foster soup’s popularity in the US.

Back on American soil, his uncle — John Campbell — invited him to join his Camden, NJ company, the Joseph Campbell Preserve Company, in 1897 as a chemist at a wage of $7.50 a week ($253 in 2022 dollars). The factory produced canned tomatoes, vegetables, jellies, condiments, and minced meats. There, Dorrance developed a commercially viable method for condensing soup by halving the quantity of its heaviest ingredient: water. Noncondensed tinned soups had been on the market for some years, but could not overcome the problem of excessive cost due to the bulky package for all that water. The rest is history, except for marketing.

Back on American soil, his uncle — John Campbell — invited him to join his Camden, NJ company, the Joseph Campbell Preserve Company, in 1897 as a chemist at a wage of $7.50 a week ($253 in 2022 dollars). The factory produced canned tomatoes, vegetables, jellies, condiments, and minced meats. There, Dorrance developed a commercially viable method for condensing soup by halving the quantity of its heaviest ingredient: water. Noncondensed tinned soups had been on the market for some years, but could not overcome the problem of excessive cost due to the bulky package for all that water. The rest is history, except for marketing.

The company’s challenge was to convince people they needed to have something they hadn’t previously realized they needed. They appealed to housewives’ thrift, social anxiety, and emotions. Campbell’s ingenuity knew no bounds. Their soup also promised to free women from being a slave to both the seasons and their kitchens.

And if time savings weren’t enough, there were the adorable Campbell’s Kids. Who could resist those two? And what mother could resist her  own brood clambering for whatever those kids in the ads were eating? Until 1916, when Campbell’s published Helps for the Hostess, canned soups were primarily marketed as, well, soups. Perhaps realizing that the demand for clam bouillon and mutton soup had its limits, Campbell’s devised new recipes. For the first time, the soups were used as recipe ingredients, rather than as stand-alone courses. The book included such “yummy” delights as “chicken jelly loaf,” made with Campbell’s consommé, cold chicken, slices of tongue and stuffed olives.

own brood clambering for whatever those kids in the ads were eating? Until 1916, when Campbell’s published Helps for the Hostess, canned soups were primarily marketed as, well, soups. Perhaps realizing that the demand for clam bouillon and mutton soup had its limits, Campbell’s devised new recipes. For the first time, the soups were used as recipe ingredients, rather than as stand-alone courses. The book included such “yummy” delights as “chicken jelly loaf,” made with Campbell’s consommé, cold chicken, slices of tongue and stuffed olives.

In a genius turn, the 64-page booklet included over 100 recipes and suggested that Campbell’s soups could be used as an alternative to “elaborate” sauces:

One of the most important and economical uses of CAMPBELL’S SOUPS is for sauces. Instead of taking time to make and season elaborate sauce, you need only use one of the many kinds of CAMPBELL’S SOUPS. Many times unattractive “left-overs” are thrown away when, by using a can of CAMPBELL’S SOUPS, they could have been made into an attractive, appetizing dish.

Packaging is also a hallmark for the product. Many stories say that Warhol’s choice to paint soup cans reflected on his own devotion to Campbell’s soup as a customer.

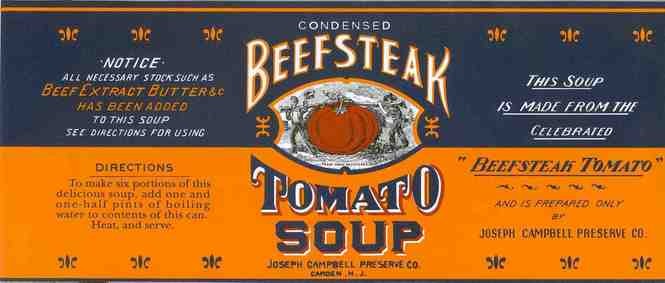

Initially, the preserve company labels were blue and orange. Numerous accounts state that in 1898, a Campbell’s executive convinced the company to adopt a carnelian red and bright white color scheme, because he was taken by the crisp carnelian red color of the Cornell University football team’s uniforms. The label’s font is said to be loosely based on Joseph Campbell’s own signature. And the medallion? It changed a few times, but the one we call grew up represents the medal for excellence the company won at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle.

Condensed soup was a hit with home cooks. The first cans sold for 10 cents a can in 1897, 12 cents is 1924 and remained under a dollar a can until 2012.